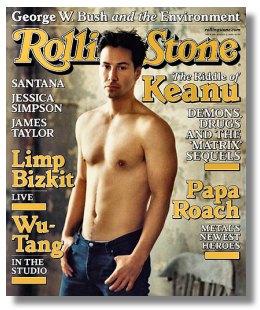

I think the first magazine I bought after really immersing myself in Keanu fandom was this Rolling Stone.

It's a really great interview. All sorts of little treats to be found, like what Rob Mailhouse says about Keanu and his bass...Bret talking about him drinking wine from a coffee cup.

Nice. Chris Heath is a good interviewer, too. Good stuff.

Read on....

The Quiet Man

Interview By Chris Heath - August 2000

While Keanu Reeves chose the most public of professions, he lives the life of a loner. Here he reveals his physical and family scars.

Keanu Reeves' first big spill came in the spring of 1988. He was a twenty-three-year-old Canadian actor, living in Hollywood, who had already shown an odd, edgy presence in River's Edge. The motorcycle accident, on Topanga Canyon Boulevard, one of the twisting links between the Los Angeles Valley and the Pacific Ocean, would leave him with a thick scar rising vertically up his stomach, out of which his damaged spleen was removed. There are many things Keanu Reeves simply will not discuss, but this is not one of them.

"I call that a demon ride," Reeves now reflects. "That's when things are going badly. But there's other times when you go fast, or too fast, out of exhilaration." He was doing about fifty when he hit a hairpin turn. "I remember saying in my head," he says, "'I'm going to die.'"

He lay on the pavement for half an hour before help arrived: "I remember calling out for help. And someone answering out of the darkness, and then the flashing lights of an ambulance coming down. This was after a truck ran over my helmet. I took it off because I couldn't breathe, and a truck came down. I got out of the way, and it ran over my helmet."

What did the experience teach you?

[Dryly] "I should have gone on the brake, released the brake a little bit, leaned into the turn."

No more abstract moral lessons?

"Now I know that if I want to take a demon ride and I don't want to die . . . then I shouldn't take it."

Did that stop you from taking demon rides?

"Yeah. Well, I had to get a couple more out of my system." Reeves smiles. "And I probably have a couple more left."

A conversation with Keanu Reeves is not always easy. He is not overtly obstructive, and he seems to make a huge effort to be polite. But there is an agony involved. For example, I ask him why he acts. For forty-two seconds, he says nothing. Not a word, a grunt, a prevarication, or a hint that an answer might come. For most of that time, his head is angled at ninety degrees away from me, as if that's where the oxygen is.

"Uh," he finally says, "the words that popped into my head were expression and, uh, it's fun."

A few minutes later, I lob a vague question about whether he ever wants to write or direct. He lets out a kind of quiet sigh. At its worst, it's like this. You ask Keanu Reeves a question and . . . just wait. Out in space, planets collide, stars go supernova. On earth, forests fall, animals screech and roar. People shout and rant and weep with anger and joy and just for the hell of it. And, all this time, Reeves sits there, entirely silent.

On this particular occasion, the silence lasts seventy-two seconds. When the answer arrives, it includes no complete sentences and adds up to a vague, unremarkable, "No, not really."

Keanu Reeves has been busy. He has four movies awaiting release and will make one more before committing himself to nearly a year and a half's work on two Matrix sequels. His band, Dogstar, has also just released an album. The first of these movies to appear, The Replacements, is a part-comic tale of some replacement football players loosely based on the 1987 NFL strike. He says that he has not seen the completed film.

"The script that I originally read and the film that was made were very different," he notes.

He agreed to it because he liked his character, Shane Falco.

"I felt like he was a good hard-luck character who gets a second chance," Reeves says.

He reminisces about a scene in the original script where the principal female lead beats up two hookers who were trying to rob Shane Falco. He really liked that. But they didn't even film it. "Didn't win that one," he says. "Tried, but . . . just didn't." He nods. "In the spirit of collaboration, the film went the other way," he says. "There's not much you can do."

I ask about one scene in which he and his teammates are in jail and begin dancing to "I Will Survive." I point out that he seemed a rather reluctant participant.

"That scene wasn't in the original script. You know . . . it was a tough one. Does it work? Is it OK?" He begins asking questions in a slightly mocking voice: "Is it romantic? Is this a slapstick? Or is the dr- . . . It's a dramedy! The new synthesis! Synthesis of form . . ." Later he points out, quite accurately, that "it feels like a period film . . . like an Eighties kind of picture. It's very traditional, the way it looks, the colors - I think it helps the film, actually, because it's like old-time good movie entertainment." As that, the film may work, but watching it, I can't shake off the feeling that Reeves is always at the film's edge, staring off into the distance, trying to find a slightly stranger and more beautiful film that never got made.

When I ask Keanu Reeves - in one of these many failed invitations to conversation - to tell me some things about him that are true, his single reply, after a certain amount of delay and discomfort, is, "I was born in Beirut, Lebanon." Back then, in the mid-Sixties, Beirut was a thriving cosmopolitan city. His mother, Patricia, was British, his father, Samuel, Chinese-Hawaiian, and this was where they lived for a while.

I ask him what he was like when he was young.

"Private," he says. "Probably a pretty private kid."

Private how? Kids are usually pretty social.

"I was pretty social, too," he says.

Private but pretty social?

"Yeah." He half-smiles. "It's a particle, it's a wave."

For his first seven years, the Reeves family moved around: Lebanon, Australia, America. By the time he was seven, he had settled in Toronto with his mother. That's where he lived until he moved to Hollywood to make it as a young actor. By then, his mother had become a costume designer. He remembers meeting Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris. "There were musicians around," he says. "I was going to music-recording studios and hanging out." Up the road, Alice Cooper was recording Welcome to My Nightmare. "I was forever trying to use their pinball machine," he recalls.

Who did you think Alice Cooper was? I ask.

"A friend of my mother's," he says.

But he looked weird and he had a weird name. . . .

"He didn't look weird to me. Not the way I grew up, man. Shit."

What do you think that kid back then wanted? Or cared about?

"Oh, gosh," he says. [When he says, "Oh, gosh," it usually marks a kind of incredulity that the preceding question has been asked.] "That's one I'll keep to myself."

Well, pulling back, what sense do you have of why you wanted to do, or ended up doing, what you did?

"Oh, I don't know. There are things I have thought about it and things I have perspective on, but for some reason I just don't want to speak about them."

Later, after communication has become easier but after he has just paused again for an eternity, I ask this: When you take a long time to answer a question, what are you thinking about?

"How to answer it," he says. "In a way that you can understand. In a way that I want to express it."

Reeves' father dropped out of the picture sometime before the move to Toronto. Reeves has previously said that they have not spoken since he was about thirteen. In 1994, his father was arrested with large quantities of heroin and cocaine, and sentenced to ten years in jail. He was released in 1996. [When Keanu and I talked nine years ago, he'd said: "Jesus, man. No, the story with me and my dad's pretty heavy. It's full of pain and woe and fucking loss and all that shit."]

Were you very conscious of not having a straightforward father figure?

"Uh, yeah."

How do you think that affected you?

"Gosh. In so many ways. I'm not filling that in, man. I'm not."

Do you have no ongoing relationship with your genetic father?

"I don't, at this time. No."

How do you deal with the trouble he gets into?

"Has there been a lot of it? I know there's some. I've heard of some."

Well, he's been in jail.

"It's his life, man. I hope he's well. Whatever that means."

Does it bother you when all that tangentially becomes part of your life?

"I feel bad that his life is affected by it, if it is. For him, it must be a drag."

People have assumed that it's you it must be a drag for.

"Oh, gosh. Not that. (Raises his voice, as if addressing the wider world) Leave him alone! Let him do his thing."

After a while, we take a rest from this dark San Francisco hotel bar and go outside so that he may smoke a cigarette. His hair is short, and he's looking smart: a black suit jacket, black everything else. Occasionally passers-by shout comments: "The Matrix! Point Break! You take care!"

He scratches his right leg, lifting his trouser to reveal a wide, curved scar. Another motorcycle accident, this one in 1996. "It's my hook, or my question mark," he says, fingering the scar tissue. "Maybe it's both. It depends on how you look at it."

How do you think of it?

"Both. It's a particle, it's a wave."

One of Reeves other movies awaiting release is The Gift, co-written by Billy Bob Thornton, a semifictionalized account of Thornton's mother's life as a small-town psychic. Most characters Reeves finds himself playing have a fair chunk of innocence at their centers, but in The Gift, which is directed by Sam Raimi, he plays a nasty wife beater called Donnie Barksdale.

"It's a part I don't get to play that often," he says. "It was a great experience." In preparation for life as a wife beater, he spent three weeks in Georgia learning how to be a redneck. "You know," he says, "Donnie motherfucking Barksdale." He got a truck, and he ended up borrowing a white-fleeced Levi jacket from a guy in a bar who told him he didn't look nearly redneck enough in his jeans and shirt. "I wanted to find out the thinking," Reeves explains. "I met this one guy, and he ended up by the end of the night beating up his girlfriend. In front of the bar."

Didn't you feel like stepping in?

"Of course. The way it happened is a long story that I'm not going to tell."

I suppose you must have been thinking, "This is great, this is just what I needed"?

"Yeah, sure."

Does that make you feel guilty?

"We're all guilty. [laugh] Do I feel guilty? I wish that didn't happen. I didn't punch her in the head. I wish he hadn't."

Reeves had been told by therapists that people who wife-beat can't access themselves emotionally, so they move straight to anger. "And that's what he did: He blew up. But then, what she did...it's a whole sick dance." Onto this train of thought he immediately appends the following oddly phrased sentiment: "But, you know, in the movies there's fake punches, and you get real feelings. It was interesting to feel that. And there was something about it. To me, it was just fun it's a really childish kind of power thing." It's a testament to Reeves; strange openness and innocence that in the same conversation where he struggles to share the most simple biographical details, he will trust that a listener will know that he means nothing too weird or offensive when he refers to acting out the behavior of a wife beater as "fun."

"We had this wonderful improv," he says. "It was Sam and I and Hilary [Swank, his wife in the movie]. Sam was, Let's figure this out in this little trailer." Reeves talks through the events in a scene in which Donnie eventually accuses his wife of lying to him, until he reaches, "And I'm, You're lying, and Sam says to me, Every time you say 'You're lying' to her, just hit her. I was like, OK. And we just started. And that's the fun of it. The exploration of what that is you're investigating the impulse of what that is and what comes out. So I'm rubbing her face, I'm choking, she's talking, we're getting in there, I'm pushing her against a wall, I'm like, 'Don't fucking look at me', and all of those things that come up, and all of those things that come up, and all of the ways that it goes, and everything that comes out for her, and the way that we bond and bind, and what we are as a couple that starts to bloom."

That must be weird, I say both fascinating and uncomfortable.

"Yeah," he says. "Yeah."

As yourself, do you express anger in active ways?

"Well, that was one of the things that came up, just figuring that out: OK, wow, I don't show anger like that. But then it comes out, and you go, Wow, I am an angry guy."

Away from acting, where does that anger stuff go in you?

"Well, you can ask that question for any emotion. With anger, it depends on the day. Why I'm angry, how I'm angry. I'm not like Donnie Barksdale. Donnie Barksdale's pretty direct, and he's someone who would use his physical aspect. Which was fun sometimes. I called it getting my Donnie on." These last four words he then repeats. "Getting my Donnie on," he says.

"I remember when we did Devil's Advocate," says Charlize Theron, who co-starred with Reeves in that move and in the one he is currently filming, Sweet November (a strange romance in which a woman announces to a man that he will spend a month, and a month only, with her). "He was living in a hotel. When we started this movie, I asked if he was still living in a hotel, and he said, No, I'm ready to put some roots down somewhere.I think, joking, he said something like, You know, the kid, the horse, the dog and the wife. The wife last. I said, I think you have it all turned around you gotta get the wife first. But I think he has changed. Before, I think he liked the idea of living out of a suitcase I think he's now learned you can be a free spirit and have the other things."

Reeves says he is looking for a place in Malibu but that he mostly stays with his sister Kim in Los Angeles, where he has his own room. (She has been fighting cancer for some years. We do not discuss this.) "I don't have anything on the wall," he responds wearily to my questions.

"Bookshelves. She gave me a desk, so I do have a desk, bottles of wine, pictures." When I inquire further, he says, "I don't really want to tell you." As for the other stuff of settling down, last year he was expecting a baby with a girlfriend. At full term the baby was found to have died in the womb.

Here in San Francisco he is staying in a hotel while he shoots Sweet November. In his room he has music: Archers of Loaf, Built to Spill, Hüsker Dü, Joy Division, Elvis Costello, Dean Martin, Bobby Darin, Dinosaur Jr, Stravinsky, Sonic Youth. And he has books. He just finished one about string theory and the origins of the universe. Now he's reading one about Alexander the Great.

After the cigarette break, we retreat to the hotel bar. Reeves requests the chair facing the wall. "I'd rather be in the dark," he says. He talks quietly, so I push the tape recorder across the table, closer to him. He pushes it back toward me. I push it back toward him again, and this time he lets it stay there.

How easily did you navigate through adolescence?

"I don't know. I didn't end up on the rope."

On the rope?

"Swinging."

After moderate success as a teen actor in Toronto, Reeves moved to Los Angeles in the mid-Eighties."The day I landed in L.A., they wanted me to change my name," says Reeves. "A studio executive called his agent," recalls Erwin Stoff, his manager for seventeen years, "and said, That's a name that will never appear on a marquee." They brainstormed a few options and eventually settled on his initials: K.C. Reeves. (Keanu's middle name is Charles.) "It only lasted for a couple of months. It's so not who I am," he says."One of the lessons."

The lesson being?

"I don't know. Other people say, 'If you want to do what you want to do, you have to do this.' And the lesson being, You know what? You don't. You don't."

It was 1989s "Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure" that first made Reeves notably famous and also sparked talk of Reeves as the Western world's dreamy hot new pinup. I suggest to him that he never seemed comfortable being a sexually attractive icon.

"Really? [Sarcastically] In Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure I was a sexual icon?"

You know the weird thing: I believe so. Even then.

"Perverts."

For a while, it was often assumed that Reeves would be forever typecast as the affable, spacey, dump California teenager and, more worrying, that anyway he had more or less been playing himself.

"That's frustrating," he says. "That's very frustrating."

A further twist was given to all this when, early in the surf-and-sky-dive thriller Point Break, Reeves character was referred to as "young, dumb and full of come," a line that was often subsequently used with glee as though it referred to Reeves himself. Asked how he felt about this, he says, "What do you think?" then free-associates: "There's something good about it, something bad, something happy, something sad. There was also another great term. What was that? Himbo.Bimbos and himbos" He laughs.

"I get no respect!" Then, with heavy sarcasm: "It drove me to drink. I was insane with grief. I would drive endless miles along Mulholland highway. It was terrible and frustrating and awful, but there was nothing I could do." At the end of this I tell him I have no idea what level of sincerity he is now talking on. "4.5," he says. Out of ten? I ask. "That I don't know," he replies.

In mainstream movies, Reeves often looks uncomfortable, as though someone has tricked him into getting out of the car right there and just driven off. Whatever the result, he has usually seemed happier when he veers away. In 1991, he made Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho, with River Phoenix, and you can still feel his pride in it. "It's a beautiful film," he says. "And lonely. The way he ends up in the street. His shoes. A stranger picking him up."

He and Phoenix became firm friends: "I enjoyed his company. Very much. And enjoyed his mind and his spirit and his soul. We brought good out in each other. He was a real original thinker. He was not the status quo. In anything."

Then I mention Phoenix's death, and Reeves looks at me as though I am the kind of person who will always spoil everything.

A month after our conversation in the hotel bar, I return to San Francisco to visit Reeves on the set of Sweet November. Today's scene is being shot in a small bay just south of the city on a wooden jetty where fishing boats dock. There are three of those cloth-backed personalized film-set chairs lined up in a row. Reeves takes the one that says liam aiken, the ten-year-old kid in the movie. He gestures for me to take Charlize Theron's, which is next to it. The chair bearing the name 'Keanu Reeves' remains empty.

He enthuses about Klaus Kinski's autobiography, a book he had previously raved about during our last meeting as "like Hemingway meets Georges Bataille. It's fantastic!" Since then, I've read it, too. And he's right. It's terrific: the most preposterously explicit, heartfelt, revealing, self-crucifying book about an actor's life one could imagine. I quote back to him one passage, in which Kinski writes, "I wish I'd never been an actor! I'd rather have been a streetwalker, selling my body, than selling my tears and my laughter, my grief and my joys."

"I love that," he hoots. "It's so funny."

[Does a deep theatrical voice] "I'd rather be a streetwalker! selling my Is that what a streetwalker does? Isn't that what an actor does?"

Could you imagine ever revealing yourself like that?

Reeves pauses, nods to acknowledge the question, then speaks.

"I imagine we reveal ourselves no matter what we do."

In the early nineties, Reeves career drifted into the doldrums. "There was a period when he really ran out of juice in terms of playing the young innocent," observes Stoff. His performance in Francis Coppola's Dracula was widely derided, by himself as well as others. "I think he just sort of lost interest," Stoff says.

When the script for Speed turned up, Reeves didn't want to do it. "I didn't understand it," he says. "I didn't quite get it." Stoff says he spent an entire twelve-hour flight between Los Angeles and France trying to persuade him. "His argument was, So what, it's a bomb on a bus. Who cares?" When they arrived in France, Reeves cracked.

"He found a reason to do it," says Stoff. "He actually fond beauty and a simplicity and grace in that character. None of that existed in the script. But he found it. What I remember him saying to me is, 'You know what, this is a guy who gets up every morning and means to do good in the world'. And I think that's what people responded to."

Though Speed was at the time, his most successful film, he seems a little uncomfortable with the attention it drew. When I ask him which of his films he feels most proud, he offers the following list: "River's Edge, Permanent Record, Bill and Ted's, I Love You to Death, Little Buddha, Tune in Tomorrow, The Last Time I Committed Suicide, The Matrix, The Devil's Advocate. I like a lot of Johnny Mnemonic. I like the version of Feeling Minnesota that's not in the movie." Speed is conspicuous by its absence.

It was not, in terms of acting, his most challenging role?

"No. While I was making it, I learned Hamlet."

Because you had room in your head?

"Yes. I had room."

So what does that tell us about Speed?

"It ain't Shakespeare."

Reeves feels strongly about his Shakespeare. There is a real boyish gusto in his voice when he talks about it. "I tend to throw out a little Shakespeare once in a while," he says. "I do love it It's like this kind of code that once you start to inhabit it with breath and sound and feeling and thought, it is the most powerful and consuming and freeing at the same time. Just, literally, elemental in sound, consonants and vowels."

He says that he knows a few sonnets and soliloquies by heart, and that he brings Hamlet with him when he travels. He has a copy here in San Francisco, presumably somewhere near the Archers of Loaf. He likes to recite parts of it out loud, alone in his room. "I love the melancholy, I guess, perhaps, of it," he guesses, perhaps.

Reeves had acted in some Shakespeare when he was younger and attended some workshops. His first high-profile brush was a Don John in Kenneth Branagh's version of Ado About Nothing. Then, in 1995, he agreed to play Hamlet onstage for a month in Winnipeg. "What I learned," he says, "is that as far as you can go, Hamlet just looks at you and goes, How about here? It's beautiful and terrifying. I feel that Hamlet is one that even great actors." He mentions, as he puts it, "Mr. Daniel Day-Lewis." Day-Lewis pulled out of Hamlet midway through a run in London, partly, it is said, due to the emotions it stirred up about his recently deceased father.

You're not a man without father issues.

"Right. What I found out in doing the play was that it brought up for me all the anger that was inside me for my mother. I mean, it surprised me, just what was there, and I hadn't seen that before."

In 1987, Keanu Reeves went down to Sunset Boulevard and bought himself a bass guitar. "I wanted to learn to play bass," he says. "I liked the sound of the bass I found my ear following it in music." He was most influenced by Peter Hook's playing in Joy Division: "It's kind of a bass line but a melody line. And kind of romantically epic, in a gothic kind of way." (Reeves Joy Division favorites: "Love Will Tear Us Apart," "Ceremony,""Atmosphere.")

A while later, he went up to a guy in a grocery store near his house, because the guy was wearing a hockey shirt, and Reeves wanted to find a local hockey game. The shirt wearer was another actor, Robert Mailhouse. The two of them started playing hockey together and then music. "He lived right under the Hollywood sign in Beachwood Canyon," Mailhouse recalls. "He had this great garage; you opened these doors and it overlooked this hillside." They would jam, sometimes alone, sometimes with friends. "I'd never met anyone who loved his bass so much," says Mailhouse. "Actually walked around the house with it." Reeves would blow up amps trying to duplicate Peter Hook's bass tones. Their first public performance was in a friend's bar. Mailhouse filched the name Dogstar from Henry Miller'sSexus. A new guitarist, Bret Domrose, joined and soon became their singer and principal songwriter. "One of the first things I remember about him," says Domrose, "is that I thought he was eccentric in a sense that he was drinking a real nice bottle of wine out of a coffee mug. Probably it was a hundred-dollar bottle of wine. It was a Montana State Highway Patrol mug."

When Domrose first suggested that they try to get a record contract, the other guys in the band said they weren't interested. Three months later, Reeves said that they were ready. A first album, Our Little Visionary, came out in 1996, though not in America. Their first American album, Happy Ending, has just been released. In Dogstar, Reeves mostly keeps his head down and plays the bass, but he also helps write the music. "He's really the most creative, melodic bass player," says Domrose. "He comes in with what he calls the Reeves ditties."

I ask Reeves: Is it just a hobby?

"I don't know. We play in a band. We fucking make music. We try to make records. We hang out. Is it a hobby? I don't know. We get paid, so isn't that professional? So, OK, I'm a professional hobbyist."

"I think he enjoys getting on the bus and traveling," says Mailhouse. "You get on and just do whatever ten guys will do on a bus. He really likes that."

"As the tour goes along," Reeves says, "one becomes more and more of a pirate. You lose a little of the civilization of it."

What are the signs that piracy is imminent?

"You start wearing a parrot on one shoulder, and a patch, and going, Arrrrrrhhhhh! Saying, Aye, matey. Thar she blows. Oh, wrong book."

"He's a really giving person," Mailhouse says.

"He'd give you his last shoe. Really smart, too. He's incredibly booksmart. He's a really interesting person who doesn't talk a lot of shit."

I ask Mailhouse how Reeves has changed in ten years.

"I don't worry about him as much," Mailhouse says. "I used to worry about him. Because I think of him as one of my best friends in the world was he going to crash his motorcycle, or this or that. We did some wild things. I guess it's just growing up. I don't know maybe it had something to do with River Phoenix, maybe. Losing someone close to him. But now I'm just proud of him. He's getting to do it the right way."

A conversation about drugs:

What role have drugs played in your life?

"One of them is, they certainly helped me to see more or have the sensation of seeing more. I guess part of the hallucinogenics of psilocybin the hallucinations or feelings one has. Sitting in a field, hearing and feeling and looking at nature, seeing what comes out of oneself. Having parts of the psyche revealed. They've certainly given me the sensation of an enrichening aspect, appreciating."

Did you ever discover any drugs you weren't prepared to take that chance with?

"No, I never had that cliche'd bad trip. But I haven't done that many drugs."

Are they ruled out of your life at this stage?

"Um, once in a blue moon."

He talks about the relationship between drugs and the government, how experimentation could be allowed without people risking harm by doing "too much of a good thing."

Have you ever felt you were doing too much of a good thing?

"Yeah, I've had a couple of days when I've been, OK, time to chill out. But that has also brought about catharsis. That is one of the human emotions to go to the dark side, to go to the light."

When Reeves was sent the script for The Matrix, he was immediately interested. He had long been a fan of comic graphic novels (Frank Miller's in particular), and he recognized that sensibility. He also liked his character's search, and the phrase "What truth?" And then there were the martial arts.

"I dig kung-fu movies," he says.

Why?

"It's just fun. Fake fights are fun." He repeats this last sentence. "Fake fights are fun. Okey-dokey."

The film's directors, Larry and Andy Wachowski, said they were looking for a maniac who would do what they needed: "And," Larry said, "Keanu was our maniac." They gave him some books to read: The Moral Animal, about evolutionary psychology; Simulacra and Simulation, by Jean Baudrillard ("Oh, it's fun! It's fun!" says Reeves); and Kevin Kelly's Out of Control, a book about machines and social systems.

"They just said, Go read, go read, go see what it does," says Reeves. "I think they gave me the phenomenal world, the internal words and the simulations that occurred in that."

In preparation for the film's unusual physical demands, which required considerable agility and skill, the actors were supposed to train for four months. For much of that time, though, Reeves was hampered. He couldn't kick because he was recovering from neck surgery. "I have a two-level fusion," he explains. "I had one old compressed disk and one shattered disk. One of them was really old, ten years, and eventually one started sticking to my spinal chord. I was falling over in the shower in the morning, because you lose your sense of balance."

Soon it will start all over again, the filming of the second and third Matrix movies in one stretch: four months of training and a year of filming. He swears that even now he doesn't know what happens in the movies. "They're devilish with how much they give out," he says. "Capricious."

Presumably they told you enough that you know it's not some incredibly weird thing you wouldn't want to be involved in?

"No."

It's totally on trust?

"Faith and trust."

So you might be wearing a pink tutu through the whole of the second movie?

"Maybe. Who knows. Hopefully."

What he does know is that the Wachowskis want the character's fighting skills to progress, hence all the new training. "Before, we fought one at a time, and I know that they want me to do five," he says. "Which is master. Thats the real deal. If you can fight five people, that's Jackie Chan, Bruce Lee stuff. So you need a whole other technique for that. You need a whole other level of proficiency, to be able to film close to real time and to be consistent and to have power on blows and to sell the punches. I'm sure theres going to be much more wire work, because the characters can fly." And he wants to learn to fight on three vertical levels: "Basically, our fights were really one level. Eye-to-eye fighting, or me going low to do a leg sweep, or me jumping in the air to kick you, that would be three levels. So I could fight low, fight middle, fight high. Then, with this one, I'll fight in the sky."

We sit side by side at the bar counter of an old fishermen's shack where they've been filming. And I ask.

Obviously it's a difficult question, but how do you feel about fatherhood now?

"I miss it."

At the end of my first visit to see Reeves in San Francisco, the uniformed man who works the door at Reeves hotel hails me a taxi. He has seen us talking and tells me, unbidden, about the man who has just left us. "He's a nice man. A nice man. You don't see him with no ladies. He's a loner. He likes his privacy. Rides a motorcycle."

Keanu Reeves still rides his bikes, and he has one here in San Francisco. That's what he likes to do when he has time off, when Hamlet and melodic bass lines and whatever other strange diversions he finds to take up his time simply aren't enough. Day or night, he'll roar out of the city. "Seeking catharsis," he'll explain. "Getting it out of the system. It helps change things."

What's the joy in going too fast?

"Too fast? Liberation."

Liberation from what?

"Going too slow."

media spot | from inside the mind of krix at December 19, 2002 12:05 PM .nice pic of keanu on the cover!

Posted by: iluvjacktraven on December 19, 2002 12:52 PM"How do you feel about fatherhood now"?

"I miss it".

Oh,tears fall out of eyes when i read that part.

This man is Pure Joy.

Thanks krix...

Posted by: Rhonda on December 19, 2002 04:15 PMI swim against the flow. :)

I didn't like because, hm, I didn't like the fatherhood question. Wow, that was the worst f***ing question ever!

Posted by: Bea on December 19, 2002 07:11 PMYeah, never a good time for a that question.

Thankfully there's so much more to the piece.

Moving on...

"-He scratches his right leg, lifting his trouser to reveal a wide, curved scar. Another motorcycle accident, this one in 1996. "It's my hook, or my question mark," he says, fingering the scar tissue. "Maybe it's both. It depends on how you look at it."

How do you think of it?

"Both. It's a particle, it's a wave."-"

I love this.

One of these days I'm going to write an epic post on that rassin'-frassin duality of his.

that is an amazing picture. good interview too, but i keep being stuck on the ... wow. epic hotness, all the way around.

you have great taste in fandom, miss krix.

Posted by: kd on December 19, 2002 09:42 PMOK, I'll admit I'm stricken for Keanu myself, but damn, he's Canadian!

All of a sudden I feel such a pride for being one myself :)

Posted by: Veshka on December 19, 2002 09:55 PMNaturally...:D

I love that pic, it's one of my favourite, favourite picture s of the Ke man!

And the article is a great read. Thanx krix!

Posted by: Keanuette on December 20, 2002 04:47 AMamen, brother keanu. going too fast is INDEED liberation from going too slow. and we *all* need that sometimes, don't we? bless you, krix.

Posted by: Lori on December 20, 2002 03:00 PMOf course there are wonderful moments, please, don't get me wrong.

"It's a particle, it's a wave" was one of the statements that gotta become a quote.

Posted by: Bea on December 20, 2002 07:22 PMyou know I have several copies of this, but I haven't read it in awhile, good way to start a slow causual sunday morning, I have come to the conclusion that it is impossible not to love him more, love the parts with bret and rob, damn, I don't have the limitations to love him (them) enough, whoa indeed.

Posted by: tess on December 22, 2002 09:46 AM"Both. It's a particle, it's a wave."

Heh heh heh. I enjoyed that line, too.

Posted by: Craig on December 23, 2002 10:46 AMRemember, this is a fan site.

Keanu Reeves is in no way connnected to this website.

Please do not make a comment thinking he will read it.

Comments are for discussion with other fans.

Thank you.